Fragment of the memoir Infancia (Innocence)

By J.A. Garcia Torres

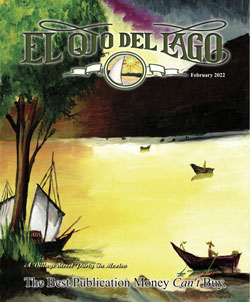

Chapala is like a strong and leafy tree. Like a yellow amate, its branches expand, grow, touch the sky, peck at the clouds; its roots sink, stick, twist; they sneak into the water, into mother earth, they latch on to the entrails of Tlali Nantli, to her matrix which is also her womb and cradle. Her lake is an inexhaustible source of life, pure fertility where the sap and cord of all things that are made to grow abound.

There are ancient families and there are new ones. In their veins they carry coca blood from our Nahuatl ancestors and also, inevitably, blood from the grim conquerors, those who had come striding from afar, destroying everything in their path, imposing themselves with a stubborn religion; with killer microbes, with daggers and primitive harquebuses. Those men had their faces red from the sun and cracked by the winds from afar. From their wiry beard, the spit that lubricated a new language dripped, full of words such as gold, corn, and land. They wanted everything for themselves. A rotten smell escaped from their boots, and from their nags’ horseshoes, a spark of agitation and fear.

A race never before seen had come to that beautiful place, superior to the natives in malice but not in spirit; their sagacity was greater but not their essence. With a roll of good intentions, they subjugated them with religions and the scourge of a distant kingdom represented by friars, soldiers, and courtiers of a crown from the Old World. The place was invaded by Spanish devils dressed as saints who stuck their tail until they populated its valleys, its hills, its mountains. Wherever they felt the heartbeat of the land, they settled. With the help of the Indians they enslaved, they dug wells in the courtyards of the houses they built; and placed knockers on the shutters with a crossbar that they never secured. They raised walls with adobe and stones they took from the mountain, then built roofs with wooden beams, palm leaves, and tiles they made with clay.

Pigs that the men in helmets had brought from afar grew fat in their pens, while they made feeding troughs to the nags the old Franciscan friars rode and built corrals where they raised cows and goats.

All who came to Chimaloacán found peace and plenty to do. This wetland had a unique climate capable of offering fruits of the earth in abundance with a fertile flora, a generous land, and an aquatic fauna to ensure sustenance for generations. The people who lived there were healthy and happy people with a peaceful mind; the men were strong and the women fertile, so the place of the shields, as the Indians called their village, grew rapidly through the years and centuries until it became home and final destination for a people that was slowly molded until it became what it is now.

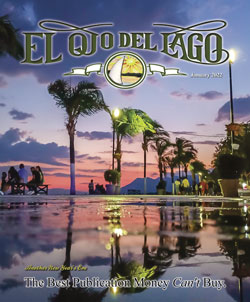

With the passage of time, miscegenation produced a new nation, the bronze race multiplied, invasions from other parts of the old continent brought other cultures. Modernity arrived bringing railroad tracks to the shores of the lake. The steel horse snorted progress in the midst of a Mexico that had recently been cut in half by invaders from the north half a century ago, and now it was beginning to divide amongst its own people. A civil revolution was in the making as a result of a rebellion against the dictatorial yoke that was trying to dispossess los de abajo, the underdogs, the peasants, of what little they had left, which was the land they cultivated to sustain.

It didn’t take long for boats to navigate the high tides of the lake and for cars to start moving from Nueva Galicia to Chapala. The industrial revolution, although late in the new continent, brought changes, among them a class society and a sense of superiority towards the darker race whose genuflection was not in perpetuity.

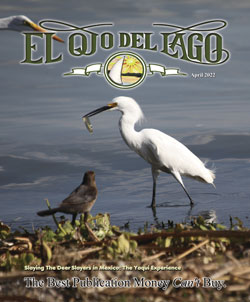

It is risky to narrate centuries in a couple of paragraphs. However, this is not a treatise on history nor a chronological document. The tree Chapala is, has gradually been taking shape, it has been growing, expanding, shedding its skin, evolving and sharing its shade with whoever comes to it. A spirit of life and happiness abounds in its core, in its trunk strength, and in its roots the wisdom that is recycled into new leaves that sprout from its robust branches. Each leaf is like the tile of a huge vault that protects those who find refuge under its thick foliage. In its branches there are always birds, their song is a perpetual concert of joy and uproar.

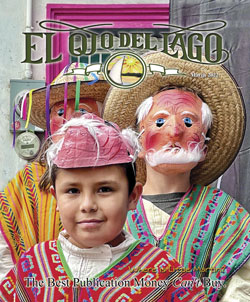

The joy of the people, then, is innate, their traditions a witness that they are relieving to the new generations so that their genuineness persists, and their culture is strengthened. That is why people who come fall in love, many stay, others promise to return.

From Innocence, a memoir (to be published)